Jane Davis is one of my newfound heroes. A prizewinning literary author who tackles the trickiest of subjects and has turned to producing the very finest self-published literary works. She’s a wonderful writer I’m cheering on full voice. She also, as you will see as she discusses her wonderful book An Unchoreographed Life, gives the most wonderful interviews!

1. Let me start with your covers – how important is it for you to maintain such a recognisable feel to your books? If you could summarise that feel, what would you say?

Branding has become hugely important to me – although I’d be lying if I said that I was fully aware of its importance when I first self-published.

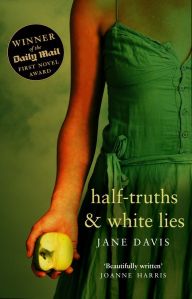

Transworld had the right of first refusal of my second novel, and they exercised it. Half-truths and White Lies was published under their women’s fiction imprint, and the manuscript I presented them with (what later became A Funeral for an Owl), was, they told me, definitely NOT women’s fiction. It may sound ridiculous to say this, but I hadn’t written either book with a particular gender bias. I didn’t – and still don’t – understand why they might assume women would want to read one book and not the other. In the light of the current campaigning against gender stereotyping in children’s fiction, to argue in favour of gender stereotyping for adult fiction seems outdated and, to be honest, more than a little insulting. My then literary agent’s reaction was, “Well, Jane. You wrote the book you wanted to write,” and I was still none the wiser.

Over the next four years, through submitting work to literary agents, I became aware that my fiction was difficult to categorise. The reason the majority gave for rejecting it was because they weren’t sure how to sell it to a publisher. As I added more manuscripts to my back catalogue, I ventured into yet more sub-categories of fiction. Perhaps my agent was right: I have written the books that I wanted to write, tackling the subjects I am most passionate about – the pioneers of photography; the divisive nature of religion; events and changes I have borne witness to. A book written for market without passion is going to lack integrity.

The brief I gave my graphic designer was that the books should look like a set you’d want to collect. I was thinking of my own bookshelves: the novels of John Irving; Frank Herbert’s Dune series; the classic Penguin paperbacks. If it were possible, I wanted that certain something that would make people say, ‘Oh, another Jane Davis’. I wasn’t starting from scratch, and so I simply borrowed elements from the cover of Half-truths and White Lies and used them as building blocks: the font and the strong photographic image, repeated on the spine.

In terms of the feel, I try to reflect the themes and the emotions of individual books. I suppose the cover for A Funeral for an Owl, which features a boy and an owl, is the most literal. I am absolutely clear in my approach about what I don’t want. My novel, These Fragile Things, tackles near-death experience and religious visions. I didn’t want to exclude readers who would normally avoid Christian fiction, because that is only one element of the book. I chose a butterfly with a broken wing, which not only fits the title and represents transformation, but also hints at vulnerability. For my new release, An Unchoreographed Life, my story of a ballerina who turns to prostitution, I was very careful to avoid any hint of erotica. Instead I wanted to give the feel of a woman living behind a mask; someone who has not quite left her past behind. That’s how I arrived at the image of a ballerina with a deer’s head.

So the key elements have to be instantly identifiable, inclusive and – I hope – intriguing.

2. Mother-child books are amongst some of the most powerful and successful in recent literary fiction – from We Need to Talk About Kevin through Room to Beside the Sea and Magda. Did you think about where your book would fit in relation to them, or as in conversation with them at all?

I’m embarrassed to say that, of those, I have only read We Need to Talk about Kevin. In the case of Kevin, I don’t think it’s possible to draw any comparisons.My main concern wasn’t where my book would sit in relation to others, but where to pitch the language for my six-year-old character when writing adult fiction. The books I turned to were What Maisie Knew, Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close, The Ocean at the End of the Road and The Night Rainbow. And the thing that they taught me is that all children are different. You can only write your character.

3. Tell me a little about your research for An Unchoreographed Life.

There were several areas: motherhood, ballet, prostitution and financial crime.

For motherhood, I researched developmental stages for six to eight year olds, but was then very much reliant on my beta readers to comment on whether they felt that the mother and daughter relationship had an authentic feel about it. Some felt that my child-character Belinda was too old for her age, some that she was too young. Some felt that my mother, Alison, was utterly irresponsible and deserved to have her child taken away from her, others that they would do everything that she did for their children and more. And so I concluded that I had written something that would invite debate.

In terms of ballet, six years of lessons in a cold church hall under the guidance of the extremely strict Miss Coral, to the accompaniment of an out-of-tune upright! Added to this, I read Meredith Daneman’s insightful biography of Margot Fonteyn. But one thing Margot Fonteyn didn’t do was retire. And so for the psychological impact of how an enforced retirement affects someone who feels that she was born to dance, I referred to personal accounts posted on the Internet. All described an identity crisis. That question: If I can’t dance, then who am I?

As with most of research, I wasn’t starting from scratch. I read histories and biographies for my own interest and, for some time, I have been compiling ‘timelines’. I add every fact I can date, so that, whenever I set my fiction, I have a record not only of historical events, but also of what was on at the theatre, what people were reading, what was making the gossip columns. And so I already had an understanding that, had I been born in another age, the chances were that I would have been either a domestic servant or a prostitute – but quite possibly, both. Prior to 1823, domestics under the age of sixteen didn’t receive a salary. They worked a sixteen-hour day in return for ‘bed and board’, a very generous description of what was actually on offer. And, in return, when they reached the age of sixteen, they were cast out onto the streets.

I grew up within the footprint of Nelson’s paradise estate. The story of his mistress, Emma Hamilton, has always fascinated me. Born into extreme poverty and forced to resort to prostitution, she later became a muse for artists such as George Romney and Joshua Reynolds and a fashionista by bucking the tight-laced trends of the day. Cast aside by an aristocratic lover, she went on to marry his uncle. Completely self-educated, Emma continually reinvented herself, mixing in diplomatic circles and becoming confidante of both Marie Antoinette and the Queen of Naples.

Added to the mix, I was gripped by a 2008 court case, when, in an interesting twist, it was ruled that a prostitute had been living off the immoral earnings of one of her clients. Salacious headlines focused on the prostitute’s replies when she was asked to justify her charge of £20,000 a week. But the case also challenged perceptions of who was likely to be a prostitute. The answer turned out to be that she might well be the ordinary middle-aged woman with the husband and two teenage children who lives next door.

Inevitably, while the project was taking shape, I read Belle de Jour. Since it was never my intention to write a book about sex, it was the everyday practicalities I wanted to understand: how the author rotated use of chemists so that she didn’t come under suspicion; her eating habits; her trips to the beauticians; which of her friends did and didn’t know what she did for a living.

Again, I used the Internet extensively to source personal accounts, diaries, blogs and newspaper reports. How did sex-workers come to the attention of the police and social services? What were the main reasons they ended up in court? (The answer was generally tax evasion and financial crime, things I knew about from my day job.) How did sex workers see themselves? How did they view their clients? How did this perception change if they stopped? I also consulted The English Collective of Prostitutes, who very kindly allowed me to quote them in my fictional newspaper article.

And then I began to imagine what life was like for the child of a prostitute. There was nowhere I could research that hidden subject. And it is always the thing that eludes you that becomes the story.

4. How hard do you find it as a writer of literary fiction to be taken seriously for your self-published books?

There are several facets to that question.

Literary fiction is a label that I continue to feel uncomfortable with. As someone who left school at the age of sixteen with an R.E. ‘O’ Level and a swimming certificate (I exaggerate), it seems arrogant to claim such a grand title, which asks readers to compare my writing with the classics or with Booker Prize winners. It can also be off-putting. Some readers – readers I think my books will appeal to – associate the term with something inaccessible and difficult, something that will have them constantly reaching for the dictionary, and my writing is anything but that. The term ‘Lit-lite’ was in vogue a couple of years ago and it tended to be applied to book-club fodder, which is really more my thing.

The difficulty is, of course, that when publishing a work of fiction, you are forced to categorise it. To me, the sub-categories are far more telling. Last week, I had one book in the Religious Fiction Kindle charts and one just outside the top 100 in the Historical Fiction Kindle charts. I am becoming rather fond of Joanne Harris’s comment that she doesn’t insult her readers by assuming they only like to read one type of fiction. We mustn’t fall into the danger of pigeon-holing readers.

As for being taken seriously, I don’t ask to be taken seriously. I would like my books to be taken seriously. The term ‘self-published’ still carries stigma. There is the lasting perception that the better indie authors are those who didn’t quite make the grade. Readers don’t understand that publishers no longer allow authors an apprenticeship; that even experienced authors with excellent sales records may be dropped if their latest book doesn’t sell. And this sea-change isn’t limited to the publishing word. I have just read in Jennifer Saunders’s autobiography ‘Bonkers’ that it’s very much the same with television. I don’t know an indie author who hasn’t had to justify his or her decision to self-publish.

Perhaps I can share these statements with you:

From a literary agent, when I declined to make changes to my books to make them more marketable: ‘You’re delving into deeper psychological territory than most fiction dares. It’s really commendable, and on a personal note, I do find it frustrating how commercialised the market is at times. I’ll refrain from the cliché we each have our cross to bear in this context.’

From a fellow indie author: ‘When I first came across you on line and saw your beautiful covers and confident, slick blog, I assumed that you were trade published, until I received the paperbacks you kindly sent me and I saw the “Made in Charleston” line on the penultimate page!’

From an interview with a book blogger: (Me) Do you think that you would be aware if the book you were reading was traditionally published or self published? (Her) Not until I started reading it – this is going to sound harsh, but if you like reading, I think you can tell if a book has been properly edited or not.

I would settle for half of Polly Courtney’s confidence. She doesn’t say that indie authors should work to the same standards as traditional publishing houses. She says we can do better.

5. Has your experience with the Daily Mail Prize helped you or hindered you in your journey?

If I’m honest, both.

Half-truths and White Lies sold 15,000 copies in a year when fiction sales took a nose-dive. That was a good result for a debut novel from a complete unknown, and I wouldn’t have been able to do that without the competition win.

Told I was going to be the Next Big Thing, my reality check came the following year with the rejection of my second novel. Though I wasn’t so naïve as to think success was going to be automatic, I didn’t expect it to be so tough to find another literary agent. In fact, the message in rejection letters was, ‘This one is not for me but, with your credentials, you’re bound to be snapped up’. I wasn’t. I’ve written elsewhere how I began to feel like the lady character in Michael Chabon’s Wonder Boys, who comes back to a writing conference held on a university campus year after year with a slightly different version of the same novel. A novel which continues to be rejected, albeit for slightly different reasons. Of course, if I had a time machine I could go back and invest my winnings in PR.

Having said that, retreating into anonymity with my tail between my legs gave me the luxury of something you can’t buy: time. If I’d been under contract, I would have had to produce a book a year. Until An Unchoreographed Life, Half-truths and White Lies was the only book that I had completed in a year. The others have taken between two and four years. Sometimes I had the right story but the wrong structure. I had time to let them rest, going back and adding layers and depth, finding new angles, different emphasis; identifying that one sentence on which the entire story pivots. When other authors say to me that they do three edits, my reaction is three? The eureka! moment might not come until the fiftieth edit. I admitted to a friend that I am nervous about my latest release, concerned that I haven’t set it aside for a year. Her response was that the risk you take being in business means that you can’t always put out your best work. That’s a sobering thought, but it applies especially to those who work to enforced deadlines. I am always in control of when I hit ‘publish’.

6. You interview some amazing writers. What is the most important thing you’ve learned from them?

I wish I could say that I have learnt how to write slick interview answers from J J Marsh, but she remains the master in that department.

Mel Sherratt reminded me that that you can’t be in the right place at the right time unless you stick at something. (She was heralded an overnight success, after she’d been quietly working away for fifteen years).

As a result of interviewing Linda Gillard, I have explored how to market myself, rather than my books, as a brand.

But, most of all, it is the fact that there is no one way of writing a novel. You discover what works best for you through trial and error. There are no shortcuts.

7. What exactly is literary fiction?

It is a box that you tick, particularly if there isn’t another that fits.

8. The literary world needs more…

Risk-takers and rule breakers. But we are nothing without readers.

9. The literary world needs less…

10. Is there one question your writing brings you back to again and again? Do you think you will ever find an answer that satisfies you?

I don’t know about a single question. It took me some time to work out that the common theme running through my novels is the influence that missing persons have in our lives. (This shouldn’t have come as any great surprise to me since the death of a friend was what made me start to write.) In my experience, that influence can actually be greater than that of those who are present. In Half-truths and White Lies it was parents who weren’t around to answer questions. In I Stopped Time, it was an estranged mother. I addressed the theme head-on in A Funeral for an Owl which considers teenage runaways. And in An Unchoreographed Life Belinda grows up without knowing her father. Fiction provides the unique opportunity to explore one or two points of view. It is never going to provide the whole answer, but it does force both writer and reader to walk in another person’s shoes. And, in many ways, it is the exploration and not the answer that is important. The idea that there is a single truth is flawed. I have a sister who is less than a year older than me our memories of the same events differ substantially. There are many different versions of the truth and many layers of memory.

11. An Unchoreographed Life is in many ways about finding the whole from the fragments. Some lives come to us in more fragmented ways than others but it strikes me that we can never have the “whole” of another person. Do you think there are ways in which having only fragments can lead to a greater understanding?

The question of whether we can ever know the whole of another person interests me. One of my beta readers made a comment to me when asked if she thought my six-year-old’s dialogue was age-appropriate. She said that we can only know what comes out of children’s mouths, not what goes on inside their heads. Of course, the same is true of anyone. We only know of someone else what they choose to reveal. My partner and I have been together for fifteen years and I know him as well as I will ever know anyone, but I don’t feel entitled to know his every thought. You have to allow each other secrets, and you have to allow each other breathing space.

I don’t allow my characters the same privacy I allow Matt. I throw them to the lions. I know what they are thinking, what they are feeling, the things they lie about, all of their secret fears. But I only meet them at a particular point on their journeys, usually in a highly volatile or unstable situation. Certainly, how people behave when under tremendous pressure can reveal a lot about them. Unfortunately, the reader probably sees my characters at their worst, but I hope that by then the reader will care about them.

12. I will have succeeded when…

My ambitions have broadened in terms of where I want to take my fiction, but are far humbler in terms of what I can expect by way of financial reward. This year I made the decision to only take on enough paid work to settle the bills and to focus on writing. And, in the same year, I have learned that only 5% of books sell over 1000 copies and that making a living from book sales is something only a few writers enjoy, and even fewer can expect to enjoy in future.

A lot is said about how essential it is to define your goals before you start writing. I disagree. I think it’s OK to have changing definitions of success. My background is business, and if it is obvious that your budget is unachievable by the mid-year point, you damned well revise it.

It took me four years to write my first novel while working full-time. My only goal was to see if I could finish a novel. To be honest, it seemed a vain ambition. It took me a long time to have the confidence to show it to anyone else but, once I started to get good reactions, I set my next goal: to find an agent. I found an agent, I set my next goal: to get published. Defining long-term goals can be off-putting if they seem like impossible dreams. There is also a danger that you may end up feeling as if you have failed personally, when the industry that we are operating within and reading trends are moving on so quickly. I find it better to take one step at a time, setting lots of short-term achievable goals. (Another 5 star review today, thank you very much.)

Over the past month, reviewers have compared me to Joanna Trollope, Dylan Thomas, Tracy Chevalier, Audrey Niffenegger, Dorothy Koomson and Rachel Hore. I’m very happy with that list.

–

Catch up with Jane

on Twitter

on Pinterest

Reblogged this on On Writing & Editing.

Very many thanks

Many thanks, Johnny. Who says that blog tours are complicated and expensive to arrange?

indeedy – they just have to have good content, which is sadly rare

Great interview, both of you! I really enjoyed “I Stopped Time” and am looking forward to reading Jane’s other novels, which look very beautiful as a set on my bookshelf – result! 😉

they make a lovely collection!

Thank you, Debbie. I have to say that An Unchoreographed Life looks stunning. Having a great cover certaintly makes you more confident to get out there and hand-sell them.

Creatively searching questions brought out deep and honest answers which made the unchoreographed life very explicit, the sort of improvised life that could rely on wise instincts. Very interesting interview which really conveyed the evolution of common themes to the body of work- absent people and their influences. Now for the books….

Very much hope you enjoy the books!

Dan certainly asks a great question. I was wondering if I would be graded on my replies, especially ‘What is literary fiction?’

Phillipa, I have realised that we met at the ALLi do and I very much admired your stunning book cover. Apologies – your profile photo is very small and my eyesight is very poor!

I love Philippa’s covers 🙂

Jane, you may be hard in sightedness but I match it hard of hearing. Small hope in a crowded room! I have only now been able to hear Hungerford Bridge properly so thanks to Alli for that. Talking of covers I think your ‘UnChoreographed Life’ has all the evocation and mesmerism of Midsummer Nights Dream…the fascination goes on and on. But I’ll stop now…

I enjoyed reading more about you, Jane. Love the questions, Dan. Thanks for sharing.

Pingback: Meet Amazing Author Jane Davis | Pills & Pillow-Talk

Reblogged this on Pills & Pillow-Talk and commented:

Today there’s a treat for you: one great author (Dan Holloway) interviewing another (Jane Davis) on his blog. After the morning I’ve had (don’t ask), I’d make a hash of trying to explain any more. You may not have heard of novelist Jane Davis before, but that could be the world’s fault for not being ready for her. So I’m off to get myself a coffee and some ibuprofen while the interview speaks for itself.

Thank you to Glynis, Phillipa and Carol. I’m so glad to have had the opportunity to meet you all recently.